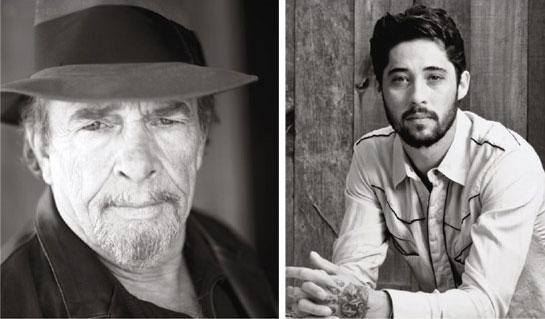

MERLE HAGGARD

Born April 6, 1937, Haggard grew up in an abandoned boxcar outside Bakersfield, raised with a post-Depression mentality by a family that had just lived through it and were still feeling its sting. The ghosts of that era shaped Haggard’s young mind, and they would play a starring role in his songs, songs that would push the Outlaw Country movement into the mainstream and land the Bakersfield boxcar boy in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

James Haggard was known to ride his horse into town and play in local honky-tonk bars, until his wife, Flossie, found religion and forced him to quit. He passed his love of music to his son, particularly of Bob Wills, whom father and son would listen to weekly on Stuart Hamblen’s broadcast out of Los Angeles. James died when Merle was only nine, and Flossie, taking extra jobs, could not control her young son, something he would repent for in the 1968 song “Mama Tried,” which hit Number One on Billboard’s Country Singles chart.

Haggard’s love of music lifted him above the turmoil in his life, which included a stay in San Quentin prison, where he saw three of Johnny Cash’s shows. After getting out of prison, he headed back to Bakersfield, living with his first wife and the son she had had with another man while he was in prison, and working for his brother digging ditches. He started playing in local country groups and eventually made his way to Las Vegas, in 1962, to back singer Wynn Stewart. He was soon discovered by Capital Records, and began touring 200 nights a year.

An amazing streak of country music followed. Haggard combined his romantic recollection of working-class life with first-hand knowledge of a life as an outlaw to define the rebellious cowboy image. Between 1965 and 1977, he had 22 out of 23 albums hit the Top Ten on the country charts. That run included the classics, Swinging Doors and the Bottle Let Me Down; Branded Man/I Threw Away the Rose; Sing Me Back Home: Same Train, A Different Time; Hag; It’s not Love (But It’s Not Bad); I Love Dixie Blues; Merle Haggard Presents His 30th Album; Keep Movin’ On and It’s All in the Movies, which all hit Number One.

Haggard clearly acknowledges the influence of legends like Bob Wills and Lefty Frizzell on his music. However, he has joined the level of influential legend, with the Dixie Chicks, Hank Williams III, Elvis Costello and many others openly citing him as an influence.

Haggard is still recording from a studio at his home near Lake Shasta, CA. Last April, he released his latest album, I Am What I Am, and he continues to tour. Today, a portion of 7th Standard Road, in Oildale, CA, right outside Bakersfield, where that abandoned boxcar used to sit, has been renamed Merle Haggard Drive and is the first thing visitors see when pulling out of Meadows Field Airport.

RYAN BINGHAM

Americana singer/songwriter Ryan Bingham, born March 31, 1981 in Hobbs, NM, was raised in the Texas border towns in and around Laredo. Poor and unhappy, Bingham left home at 17, escaping a difficult family life (“We moved a lot”) and became self-supporting. In what would be a turning point in his life, he learned the rudiments of guitar from a Tejano neighbor who taught the teenaged Bingham “La Malagueña.” Moving from one relative to another, crashing with friends or living out of a truck, he supported himself by rodeoing and construction work until he moved north to Stephenville, TX, where the deep singer/songwriter roots spoke to Bingham, and he began playing regularly in honkytonks, among them The Halfway Bar, a roadhouse owned by his uncle.

Bingham worked bars and self-released his albums until Lost Highway took notice and released 2007’s Mescalito and Roadhouse Sun (2009), both produced by former Black Crowes guitarist Marc Ford. Later that year, producer/songwriter T Bone Burnett solicited Bingham to contribute music to the film Crazy Heart, and cast Bingham and his Dead Horses band as a pickup band playing in a bowling alley. Burnett’s certainly got the ear: “The Weary Kind” won a Golden Globe and Academy Award for Bingham and Burnett.

In the wake of his success, Bingham’s new album, Junky Star, is more of the same: great—albeit somewhat dark—lyrics falling somewhere in the overlapping spheres of 1940s and ’50s country (Hank Williams), folk (Woody Guthrie) and Chicago blues (Muddy Waters). He’ll be touring out West with Willie Nelson when Junky Star comes out and making East Coast appearances later in the fall. When Elmore suggested that he’d have fewer bad times to draw on in the future as he spent more time by the pool, Bingham laughed good-naturedly. “I hope my life becomes better and happier, and I hope I got those things behind me. Maybe I’ll have to find something to say about a fruity drink with an umbrella.”

The songs on Junky Star were written over the past year or two, and, as a rule, were recorded live in one or two takes. Part of that decision was Burnett’s, but Bingham, predictably, also wanted to keep it real and raw, and that they did.

![]()

Elmore: What are you listening to right now?

Merle Haggard: You wouldn’t believe it. I’m studying a breakdown fiddle tune called “Soppin’ the Gravy.” I’ve got about seven or eight versions of it, and I’m trying to learn it on the fiddle. It’s a real neat tune. A lot of contests have been won with it. It’s pretty tough.

Merle Haggard: You wouldn’t believe it. I’m studying a breakdown fiddle tune called “Soppin’ the Gravy.” I’ve got about seven or eight versions of it, and I’m trying to learn it on the fiddle. It’s a real neat tune. A lot of contests have been won with it. It’s pretty tough.

Ryan Bingham: Right now, Bill Withers, Live at Carnegie Hall. In general, everything from Bob Marley to Bob Wills.

EM: What was the first record you ever bought?

MH: Probably a Hank Williams record. I was 11 or 12. Television hadn’t hit the West Coast, so radio was still in charge. What I was listening to on the radio was the full gamut of pop music and what they called hillbilly music at that time. There was no such word as country. It was hillbilly or it was pop. We were living in Oildale, CA, in a converted refrigeration box car. We heard this Hank Williams guy and we bought some records because Mama bought a new little player that set up on top of the old stand-up radio.

RB: My Uncle Dave had old vinyl records I used to listen to all the time—Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen, the Rolling Stones. The first thing I ever asked for might have been Creedence Clearwater.

EM: Where do you buy your music?

MH: All the obvious places. To find “Soppin’ the Gravy,” you go to the box sets of people that you know recorded that kind of music. You go to the Internet, to collectors and every place you know. You go to the archives at CBS. Amazon, or to a local Mom and Pop, or Best Buy, if it’s necessary.

RB: When we’re touring on the road, we’re playing little bars or theaters, downtown areas, we always look for those Mom and Pop shops, those local indie record stores, and try and support that as much as we can. Other than that, go online.

EM: What was the first instrument you played?

MH: My mother gave me violin lessons when I was about eight years old, and I took six lessons. I learned as little as I could about reading, how to hold the bow and how to keep from squeaking the fiddle and that was about all. It didn’t interest me at all at that point. Guitar was where my heart was at. I went back to it when I decided that I needed two fiddles in my band, and the guys that were good enough to play in my band wanted too much money. So I had to learn to play it myself.

RB: My mom had bought me a guitar for my 16th birthday, and I just had it sitting around in the closet for a couple of years until we moved down to Laredo, TX, and some friends of my parents could play the guitar, and showed me a few chords and how to actually play it. I kind of stuck with it.

EM: What brought you to the instrument you now play?

MH: About the time I was nine, I was learning a chord or two on the guitar. Then I pretty much stayed with the guitar all the way through until I was 33 and I jumped back on the fiddle. It took me seven years of twelve hours a day of learning what I wanted to learn on the fiddle. That’s definitely a challenge I’ll never forget.

RB: I’m still with the guitar and harmonica, but my mother-in-law gave us a piano and so we’ve got one in the house now, so I’m picking it up.

EM: Who would you like to write with that you haven’t?

MH: I’m really not a co-writer. If you write with somebody then you’ve got to sit down with the subject. The only way I’ve been able to do that is I’ll write some words and maybe the melody didn’t come with the words and I’ll hand it to one of the guys and the band and say “Go write me a melody with this.” That’s about the only way I co-write.

In the early days I did some co-writing with Tommy Collins, but Bonnie Owens was the lady with the pen, and I gave her the words to write down. My songs don’t come from sweat, they come from somewhere above, so I don’t know when they’re going to come. It’s definitely not that I sit down and say, “Okay, I’m going to write a song about a caboose.”

RB: Jeff Tweedy, who plays with Wilco. I’ve been a fan for a while and like what they do. Seems like they’re kind of open to anything, and I like to experiment.

EM: What musician influenced you most?

MH: Bob Wills. He influenced Grady Martin who influenced me on guitar, and then when I came back to fiddling he influenced me again. It’s just his touch on the fiddle, lifted by Grady and put on the guitar. Grady was my favorite guitar player so it kind of goes back to Wills. The musicians who have worked with me are certainly influential in my life, and it’s an array of great players like Grady Martin, Reggie Young, Chet Atkins, James Burton and the list goes on of great players. I try to pick up a little from everyone.

RB: A lot of the old blues stuff, guys like Blind Willie Johnson, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, that style really hit me the most, that stuff with that raw emotion. And a lot is the singer/songwriter guys out of west Texas I felt like I could relate to: Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark. Joe Ely, Steve Earle is a big one, Bob Dylan, John Prine, a lot of the folk singer/songwriters.

EM: What was the song or event that made you realize you wanted to be in music?

MH: I was on the road in Zion, IL. I played this bad honkytonk, and the band was bad and just knew how to play in a few keys. I had two or three other dates left on that tour and I cancelled them. I told my good friend Dean Holloway, “Dean, the next time you see me out here on the road I’m going to have my own band. I can’t do this out here with these rinkydinks anymore.” So we were driving, it was in the year of ’64, and we had a brand new ’65 Pontiac station wagon and we went home and I formed the band that’s still with me. That’s probably the financial move of my life that was towards being in it forever. Now you’re responsible for other people, too.

RB: When this guy was showing me how to play this old mariachi song, “La Malagueña,” he was showing me one part at a time, something hit me and captured my attention. It was a relief to be able to express myself through that music, and it was something that nobody could take away from me. I stuck with it. We moved a couple months after, and he was gone.

At the time, my family life wasn’t too great. I moved up to Stephenville, TX, and started going to some local bars. In those days, in those border towns, the only kind of music you could hear live were Tejano or mariachi groups. It wasn’t until I got back up around Ft. Worth where you heard the college circuit, like Robert Earl Keen, once I was introduced to that whole world of music, I thought, Man, I ought to do something like this. Other than that, I could work a job 8 to 5, doing construction or digging holes so this was my way out of that. I wouldn’t have anyone to answer to but myself. If I could make 50 bucks a day in tips playing in some shithole bar, that was certainly better than getting up at 5 in the morning and listening to some…uh…jerk yell at me, carry stuff, and make 50 bucks…maybe.

EM: Who would you like in your rock and roll heaven band?

MH: I’d have Roy Nichols and Jenks Carman on twin guitars. Jimmy Gordon on drums and probably Dennis Hromack on bass, he was my bass player for years, and Ralph Mooney on steel guitar. Glen Campbell would be singing harmony and playing rhythm guitar. Fiddle we’d have Johnny Gimble and Joe Holley, and I would probably have to have Millard Kelso on piano.

EM: You don’t want Bob Wills in your band?

Bob Wills is a leader. He has to have his own band. Leaders don’t follow well. You can’t control Bob Wills or Miles Davis; they’re on their own.

RB: The band I got is pretty damn good. Gosh, I’d rather put together a band just to listen to, not to be a part of. John Bonham on drums, Jimi Hendrix on guitar. Roy Orbison singing, Paul McCartney playing bass, maybe John Lennon playing keys. Levon Helm playing percussion and drums with John Bonham, that would be awesome. Have to have Keith Richards in there, too. How big is this band, anyway? On vocals, Buddy Holly, Aretha Franklin or Nina Simone. We’d have to have a horn section, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band; maybe Dr. John on more piano. Smokey Robinson’s gotta be in there. And Bob Wills and Tommy Duncan on the fiddle, get a couple fiddles in there. I’d be playing harmonica if they’d let me. Then some high school marching band—we’d need some kids in there.

EM: What’s your desert island CD?

MH: Probably a Bob Wills box set. You get Tommy Duncan singing—Bob was a good singer, but he was a stylist and Duncan was a great jazz singer and a crooner also.

RB: Bob Marley’s Greatest Hits. It’s one CD that never gets old. Even if it gets old, you can pick it up a few days later, and it puts you right back in that place again.

[…] Grady Martin and Hank Garland are at the top of my list of guitar heroes. Their genius graces the records of many classic hits. The songs of Red Foley, Johnny Horton, the Johnny Burnette Trio, Elvis Presley, Brenda Lee, Patsy Cline and Roy Orbison all bear the mark of these studio heavyweights. Though their style is generally regarded as a mash up of jazz, bebop, country and blues I’ve often wondered who specifically influenced them. What artists did they listen to and where did they turn for inspiration? As a musician and historian I could not leave these questions alone. My search for an answer turned up an interview with Merle Haggard in which he said that fiddle legend Bob Wills was a major influence on Grady. “He influenced Grady Martin who influenced me on guitar, and then when I came back to fiddling he … […]

[…] styles are varied and never contrived. In a 2010 interview with Elmore Magazine, Bingham cites his influences as “Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark. Joe Ely, […]